A gig held at The Lanes on Sunday 13th November. The event starts at 19:30.

18+ event.

--

Dominic Gore is part of a rich tradition of distinctly British disruptors. As inspired by the unvarnished portraiture of Martin Parr as he is Ballardian grotesquerie - and by the seedy witticisms of Jarvis Cocker as he is the arch commentary of Neil Tennant - his solo debut skewers notions of national identity with a vivid mix of pin-sharp satire and self-lacerating candour, all steeped in an expansive palette synthesising new wave, sophisti-pop, and art-rock.

Ask the south London singer-songwriter about All These Things ’gestation, and he’ll tell you of two years of intense toil, of forging relationships with collaborators remotely, of the painstaking process of recording up to 200 instruments per song. The truth is the album’s roots extend significantly further, way past his work in the band Little Cub, beyond even his very earliest songwriting experiments, and back to his childhood, growing up in an unremarkable commuter town on the edge of the M25.

Both of his parents were professional musicians, his mother being one of the first people to teach classical guitar at a conservatoire, and his father a conductor working with touring companies including the Vienna Festival Ballet. When they separated, music became the medium through which Gore would attempt to bond with his father, frequently accompanying him on pilgrimages to the classical department of Tower Records in Piccadilly Circus.

Despite their best efforts an underlying friction remained, and when Gore dived headlong into synth-pop as a teenager it was in part a way of rebelling against the perceived pomposity of his father’s tastes. “We'd have these sort of very protracted conversations in the car where I'd be arguing why Ace of Base was better than Tchaikovsky,” Gore grins. “I mean, I gave it a damn good shot.”

Having already been introduced to Depeche Mode, Yazoo and Daniel Miller via his step-sister’s husband, it was his discovery of the Pet Shop Boys that would prove most pivotal in shaping his own musical vocabulary. Borrowing a copy of singles compilation Discography from a neighbour, Gore was instantly obsessed, and not least because it seemed to inhabit an entirely different universe to the pop-punk and nu-metal acts dominating conversations at the time.

Growing up, Gore always felt somewhat out of step with the rest of society. Raised without a TV until his early teens, he didn’t possess the pop culture lexicon of his peers, and thanks to behavioural issues he spent much of his early adolescence moving between schools. It was only when he won a scholarship to a school with a strong arts focus that he began to find his feet, gaining a grounding in classical and jazz, and subsequently leaving Leatherhead to study music in London.

Still, Gore never composed an original song until his early 20s, when he was shaken into songwriting by the shock of losing his mother. “Her death really came out of nowhere,” he recalls. “And when the funeral came around, I couldn't really play a lot of the music that she liked, because it was too painful. So I just wrote this song to perform because I didn't really know what else to do. And then afterwards it was like, ok I'm a songwriter now: that's what I do.”

Gore pursued this interest in private for much of his 20s, sharing sketches with select friends, who by turns encouraged him in his vision. The most significant of these were Ady Acolatse and Duncan Tootill, who went on to become Gore’s collaborators in synth-pop outfit Little Cub. Synthesising shared influences including New Order, Aphex Twin and DFA Records, together they released one album (2017’s Still Life), before disbanding in 2019, following the release of ‘Millennium People’, a standalone single that would prove the final word in one chapter and the prologue for the next.

A reinvigorated version of the track opens All These Things, its richly-layered arrangement bringing renewed power to the song’s fantastically dystopian imagery. “Maybe it’s time the great British lifeboat capsized,”Gore wonders idly in the chorus, before the song climaxes in a twinkling tapestry of electronics and propulsive beats.

Where Still Life found Gore focused almost exclusively on analogue synths, for All These Things he was equally drawn to organic textures. Largely self-produced, with additional support from former band mate Tootill, it sees him broadening his palette to create a more expansive and impactful sound, be that the colliery band brass opening ‘I Like You’, the wistful sax low in the mix on ‘Need You Tonight’ or the plaintive piano chords and distorted guitar powering ‘Bodies’.

Spiritually, it’s a shift akin to the Pet Shop Boys’ development between Introspective and Behaviour: from bright, dancefloor-focused pop to melancholic mini-symphonies.

This pensive feel is further reflected in starkly rendered - and often blackly humorous-stills reflecting the disappointing reality of British culture, from men in “sweaty Speedos,” to “rows of soaking sausage rolls”. Gore insists these dank depictions come from a place of affection rather than repulsion, and from a long-held fascination with what he describes as “the very English phenomenon of failure.” He displays a startling lack of self-preservation too, sending up his own image on ‘California’ (“Just because I’m reading Rousseau / Doesn’t mean I can’t quote Scrubs”), and offering up humiliating details for public consumption on ‘Bodies’.

For Gore, this gut-led lyrical approach is non-negotiable: it’s the connective tissue that unites an artist with their audience. “It means a lot to me not to hide anything becau se it creates this tapestry of a shared language.”

“I remember sending [‘Bodies’] to my publisher,” he laughs. “He was like, ‘First off, you know, this song is quite disturbing - are you okay? And secondly, are you sure you want to put this out?’ But the grotesque nature of the English satirical spirit has always appealed to me. When people talk about JG Ballard, they focus on the sexcapades or the violence, but actually a lot of it is just about a guy who's quite embarrassing, or a bit doddery, and not really understanding what's going on.”

And yet, for all the apocalyptic imagery in ‘Millennium People’ and faded glamour of a song like ‘Set You Free’, there is hope to be found amongst the rubble. When Gore sings, ‘Maybe it’s time to give in and start living,” on the title track, it’s emblematic of someone no longer in thrall to idealism, but determined to make the most of the moment, whatever the reality.

As Gore explains, “It's a very real possibility that we might be living in the end times, you know? This might be how we're going to go out. And we've got this incredible opportunity to experience life, so why not make the most of it? Literally anything could happen right now.”

Entry requirements:

--

Dominic Gore is part of a rich tradition of distinctly British disruptors. As inspired by the unvarnished portraiture of Martin Parr as he is Ballardian grotesquerie - and by the seedy witticisms of Jarvis Cocker as he is the arch commentary of Neil Tennant - his solo debut skewers notions of national identity with a vivid mix of pin-sharp satire and self-lacerating candour, all steeped in an expansive palette synthesising new wave, sophisti-pop, and art-rock.

Ask the south London singer-songwriter about All These Things ’gestation, and he’ll tell you of two years of intense toil, of forging relationships with collaborators remotely, of the painstaking process of recording up to 200 instruments per song. The truth is the album’s roots extend significantly further, way past his work in the band Little Cub, beyond even his very earliest songwriting experiments, and back to his childhood, growing up in an unremarkable commuter town on the edge of the M25.

Both of his parents were professional musicians, his mother being one of the first people to teach classical guitar at a conservatoire, and his father a conductor working with touring companies including the Vienna Festival Ballet. When they separated, music became the medium through which Gore would attempt to bond with his father, frequently accompanying him on pilgrimages to the classical department of Tower Records in Piccadilly Circus.

Despite their best efforts an underlying friction remained, and when Gore dived headlong into synth-pop as a teenager it was in part a way of rebelling against the perceived pomposity of his father’s tastes. “We'd have these sort of very protracted conversations in the car where I'd be arguing why Ace of Base was better than Tchaikovsky,” Gore grins. “I mean, I gave it a damn good shot.”

Having already been introduced to Depeche Mode, Yazoo and Daniel Miller via his step-sister’s husband, it was his discovery of the Pet Shop Boys that would prove most pivotal in shaping his own musical vocabulary. Borrowing a copy of singles compilation Discography from a neighbour, Gore was instantly obsessed, and not least because it seemed to inhabit an entirely different universe to the pop-punk and nu-metal acts dominating conversations at the time.

Growing up, Gore always felt somewhat out of step with the rest of society. Raised without a TV until his early teens, he didn’t possess the pop culture lexicon of his peers, and thanks to behavioural issues he spent much of his early adolescence moving between schools. It was only when he won a scholarship to a school with a strong arts focus that he began to find his feet, gaining a grounding in classical and jazz, and subsequently leaving Leatherhead to study music in London.

Still, Gore never composed an original song until his early 20s, when he was shaken into songwriting by the shock of losing his mother. “Her death really came out of nowhere,” he recalls. “And when the funeral came around, I couldn't really play a lot of the music that she liked, because it was too painful. So I just wrote this song to perform because I didn't really know what else to do. And then afterwards it was like, ok I'm a songwriter now: that's what I do.”

Gore pursued this interest in private for much of his 20s, sharing sketches with select friends, who by turns encouraged him in his vision. The most significant of these were Ady Acolatse and Duncan Tootill, who went on to become Gore’s collaborators in synth-pop outfit Little Cub. Synthesising shared influences including New Order, Aphex Twin and DFA Records, together they released one album (2017’s Still Life), before disbanding in 2019, following the release of ‘Millennium People’, a standalone single that would prove the final word in one chapter and the prologue for the next.

A reinvigorated version of the track opens All These Things, its richly-layered arrangement bringing renewed power to the song’s fantastically dystopian imagery. “Maybe it’s time the great British lifeboat capsized,”Gore wonders idly in the chorus, before the song climaxes in a twinkling tapestry of electronics and propulsive beats.

Where Still Life found Gore focused almost exclusively on analogue synths, for All These Things he was equally drawn to organic textures. Largely self-produced, with additional support from former band mate Tootill, it sees him broadening his palette to create a more expansive and impactful sound, be that the colliery band brass opening ‘I Like You’, the wistful sax low in the mix on ‘Need You Tonight’ or the plaintive piano chords and distorted guitar powering ‘Bodies’.

Spiritually, it’s a shift akin to the Pet Shop Boys’ development between Introspective and Behaviour: from bright, dancefloor-focused pop to melancholic mini-symphonies.

This pensive feel is further reflected in starkly rendered - and often blackly humorous-stills reflecting the disappointing reality of British culture, from men in “sweaty Speedos,” to “rows of soaking sausage rolls”. Gore insists these dank depictions come from a place of affection rather than repulsion, and from a long-held fascination with what he describes as “the very English phenomenon of failure.” He displays a startling lack of self-preservation too, sending up his own image on ‘California’ (“Just because I’m reading Rousseau / Doesn’t mean I can’t quote Scrubs”), and offering up humiliating details for public consumption on ‘Bodies’.

For Gore, this gut-led lyrical approach is non-negotiable: it’s the connective tissue that unites an artist with their audience. “It means a lot to me not to hide anything becau se it creates this tapestry of a shared language.”

“I remember sending [‘Bodies’] to my publisher,” he laughs. “He was like, ‘First off, you know, this song is quite disturbing - are you okay? And secondly, are you sure you want to put this out?’ But the grotesque nature of the English satirical spirit has always appealed to me. When people talk about JG Ballard, they focus on the sexcapades or the violence, but actually a lot of it is just about a guy who's quite embarrassing, or a bit doddery, and not really understanding what's going on.”

And yet, for all the apocalyptic imagery in ‘Millennium People’ and faded glamour of a song like ‘Set You Free’, there is hope to be found amongst the rubble. When Gore sings, ‘Maybe it’s time to give in and start living,” on the title track, it’s emblematic of someone no longer in thrall to idealism, but determined to make the most of the moment, whatever the reality.

As Gore explains, “It's a very real possibility that we might be living in the end times, you know? This might be how we're going to go out. And we've got this incredible opportunity to experience life, so why not make the most of it? Literally anything could happen right now.”

Entry requirements:

Other indie pop gigs

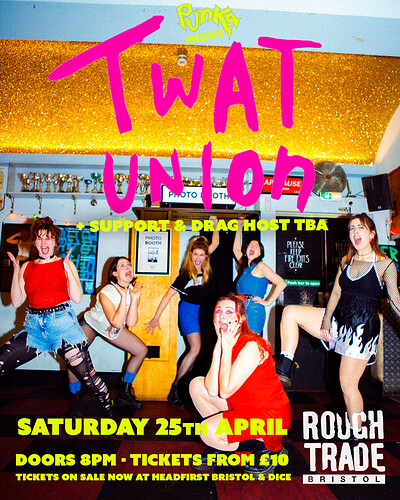

— Rough Trade Bristol

pop

lgbtq+

punk

alternative pop

drag